Featured Post

Maintaining Your New California Garden: Life-friendly Fall Pruning

Mother Nature's Backyard in November: illustrating life-friendly fall pruning. Late fall and early winter are important prun...

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Theodore Payne Garden Tour - Next Weekend

The Theodore Payne Garden Tour is this coming weekend (Mother Nature's Backyard is open on Saturday as part of the tour). If you haven't got your tickets yet, see: http://www.nativeplantgardentour.org/

Sunday, March 13, 2016

Spring Native Plant Sale - Edible, Medicinal & Useful Plants

Tuesday, March 8, 2016

Plant of the Month (March) : Narrowleaf bedstraw – Galium angustifolium

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - Mother Nature's Backyard |

An

overall dry winter, with occasional bouts of rain, has many plants confused as

to season. Hard to blame them; we’re a bit confused ourselves. One perennial that’s getting ready to bloom is

the Narrowleaf bedstraw, Galium

angustifolium. Its cheery flowers

can be seen this month in both Mother Nature’s Backyard and the Garden of

Health.

Around

40 species of bedstraw are native to California, according to CalFlora [1]. In addition to Galium angustifolium, the following are native to Western Los

Angeles County: Phloxleaf bedstraw (Galium

andrewsii), Common bedstraw (Galium

aparine), Box bedstraw (Galium

buxifolium – Channel Island species), Santa catalina island bedstraw (Galium catalinense – Channel Island

species), Santa Barbara bedstraw (Galium

cliftonsmithii), Climbing bedstraw (Galium

nuttallii), Graceful bedstraw (Galium

porrigens) and Threepetal bedstraw (Galium

trifidum). The most common locally are Galium angustifolium, G. aparine,

G. nuttallii and G. porrigens. An

additional 9 or 10 species can be found in the San Gabriel Mountains of Los

Angeles County.

Galium angustifolium is one of the most common bedstraws

in S. California and Baja California, Mexico.

It includes eight recognized sub-species, some of them narrow endemics. Like

most California bedstraws, Galium

angustifolium is an herbaceous perennial.

Amongst the California species, only 4 are annuals, and a few others are

large enough to be called shrubs or vines.

If you want to plant a

bedstraw in your garden, Narrowleaf bedstraw is a pretty good representative

species.

The

genus Galium, which is found in

temperate climates throughout the world, is one of the larger genera in the

Family Rubiaceae, the Madder or Bedstraw

Family. While bedstraws were well known in past eras, they are little remarked

upon today. They are not as showy as

some of the better known California natives, and their useful attributes have

fallen out of favor. So while they are

common – you’ve no doubt seen them when hiking in the local mountains – they

don’t receive much press today. And

that’s a shame, since they are good little garden plants.

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - growth form |

Narrowleaf

bedstraw is a rather delicate-appearing perennial or sub-shrub that grows to 1-3

feet tall and 2-3 feet wide. It is

notable for its many slender branches and narrow leaves, which give the entire

plant an open appearance. The general shape is mounded to slightly sprawling. The bases of the branches become woody; the

ends are always herbaceous.

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - foliage |

The

leaves are very narrow, bright green becoming medium green, arranged in whorls

of four at intervals along the stems. The number of leaves per whorl – and its

perennial lifestyle – distinguish it from the Common bedstraw, an annual with

six to eight leaves per whorl. With

summer water, Narrowleaf bedstraw can be evergreen; in water-wise gardens like

Mother Nature’s Backyard, it becomes dormant during the dry season (usually

about August). You can cut it back then,

or just leave until the fall pruning season.

It quickly leafs out and grows in early spring.

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - flowers |

Narrowleaf

bedsraw blooms in the spring – anytime from March to May in western Los Angeles

County. The plant is dioecious; male and

female flowers grow on separate plants. That

means you’ll need at least one of each in a garden to produce viable

seeds. The two flowers look similar:

both are small, yellow-green to pale yellow, in dense clusters. In a good year,

plants will be covered in blooms (see above). The mature flowers are hairy, as

are the seed capsules - small nutlets with straight, bristly hairs (which allow

them to latch onto passing animals for distribution). We’ll try to get some good nutlet photos this

year.

|

| Galium angustifolium seed capsules |

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - foreground in front of 'Howard McMinn' manzanita |

Narrowleaf

bedstraw is not at all picky or difficult to grow. In fact, it’s much sturdier than you might

guess from its appearance. While this

species normally grows in rocky, well-drained soils we’ve have no problems with

it in clays. It likes some afternoon

shade in hot gardens, and does well in high shade or to the east of larger

shrubs. It can take anything from moderate

to infrequent water. We prune ours back

to about 8 inches in the fall to encourage a bushy shape. That’s just about all the management that’s

needed.

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - Mother Nature's Backyard |

We

love this plant as a filler in gardens that range from informal to

semi-formal. It’s an excellent choice

for mid-beds, where its green foliage and flowers are appreciated in spring. The foliage provides a nice contrast to garden

shrubs (see above). There really is

nothing that looks quite like this plant.

In

the past, the dried foliage of Galium species was used to stuff straw

mattresses, imparting a fresh, sweet scent.

We’ll dry some and try it in a natural pillow. Galium

angustifolium is likely utilized as a larval food by several moth

species. We’ll try to keep an eye out

for caterpillars and update with our findings.

A tea made from the foliage, with

or without flowers, was used as a traditional medicine for diarrhea by the Kumeyaay

or Southern Diegueno Indians [2]. The

foliage could be used fresh or dry. We’ll

dry some and give it a try when the need arises!

|

| Narrowleaf bedstraw (Galium angustifolium) - young plant in the Garden of Health |

In

summary, Galium angustifolium is an

interesting filler plant suitable for S. California gardens. It’s green foliage and cheery blooms are a

welcome sight every spring. It can be

tucked in around shrubs, and it’s rumored to have both habitat and medicinal

value. For some reason, we’re captivated

by this unassuming little plant – and hope you will be too.

For a

gardening information sheet see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/gardening-sheet-galium-angustifolium

For more

pictures of this plant see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/galium-angustifolium-web-show

For plant

information sheets on other native plants see: http://nativeplantscsudh.blogspot.com/p/gallery-of-native-plants_17.html

- Calflora - http://www.calflora.org/cgi-bin/specieslist.cgi?where-genus=Galium

- http://nathistoc.bio.uci.edu/Plants%20of%20Upper%20Newport%20Bay%20(Robert%20De%20Ruff)/Rubiaceae/Galium%20angustifolium.htm

We

welcome your comments (below). You can

also send your questions to: mothernaturesbackyard10@gmail.com

Monday, February 29, 2016

Winter Drought? You’ve Just Gotta Water

Strong

El Niño conditions in the Pacific.

Plenty of rain and snow in Northern California and the Sierras. But here in Southern California – and

particularly in western Los Angeles County – gardeners are wondering ‘where’s our El Niño?’ Instead of record rains, we seem to be

entering our 5th year of drought very early this year. And a dry winter means you’ve just got to water your

native plants.

Many

Southern California native plants are really drought tolerant. You can read

about why at: http://mother-natures-backyard.blogspot.com/2015/10/how-things-work-plant-drought-tolerance.html But plants from western Los Angeles and

Orange Counties need at least 10 inches of winter rain (or irrigation) to

survive. Winter rains are what make our

local plants both water-wise and lovely.

The rains allow them to cope with

our long, hot, dry summer and fall.

Southern

California homeowners are struggling to meet their targeted 25% reduction in

water use this winter. Local water

companies recently bemoaned our 17% reduction compared to 2013. Which leads us to wonder: ‘Have they looked

out the window?’ It’s dry this winter;

and most of us don’t want to lose the mature trees and shrubs that shade and

cool our neighborhoods. And so we water.

Plants

from Mediterranean climates are the best-suited water-wise plants for our

region. They should dominate our home and commercial landscapes. Many are very water-wise in the summer/fall,

when we most need to conserve water.

They can result in significant yearly

water savings when used to replace summer-thirsty tropical plants and

wet-climate grasses. In fact, they

are more water-wise than the semi-tropical succulents many people are now

planting to conserve water. So water

agencies, state officials and teachers should be encouraging gardeners to plant

water-wise Mediterranean climate plants, and most importantly, California

natives.

But

local water companies don’t yet seem to understand that Mediterranean climate plants,

including Mediterranean herbs and citrus trees, must be watered in dry winters.

And some dry winters are to be expected

in in Southern California. Ideally,

water budgets should take year-to-year variability into account; computerized

data allow water agencies to do so.

A

‘one size fits all’ approach to water conservation doesn’t make sense in times

of rapid climate change. Our current

water targets are based on 2013 monthly water use levels. And the 2012/2013 season, while dry

over-all, started with a fairly normal winter (in which little supplemental

water was needed). We were gardening along with the rest of you

in 2013. So we know: our soils were

moist well into spring that year without supplemental water.

Some

of us have been given ‘water budgets’ that specify the number of CCFs we can

use each month (based on a 25% reduction from 2013 levels). A CCF is hundred cubic feet of water (the first ‘C’ is the

Roman numeral for 100); one CCF is equivalent to 748 gallons. Five CCFs per month is about the lowest

feasible level if you have any sort of a garden at all. A small family can get down to 3-4 CCFs per

month with vigilant indoor water saving and almost no outside water use. But it’s not easy to keep a garden going on 5

CCFs per month during a significant winter drought.

Fortunately, some water companies allow customers to

‘bank’ CCFs not used. If your garden

features native/mediterranean plants, and if you follow our suggestions for

surviving the drought (see http://mother-natures-backyard.blogspot.com/2015/07/surviving-drought.html),

you can actually save excess CCFs for winter drought watering. But even if you don’t have saved credits, you

can keep your winter water use reasonable, while still maintaining healthy

plants. Here are a few suggestions:

- Save as much water

indoors as possible. Many of us still take sponge baths most

days, wear our outer clothes longer between washings and use rinse water

to fill our toilet tanks and water our plants. Water

saved indoors can be used to water your garden plants.

- Prioritize your

watering. Don’t

waste water on plants that need replacing.

Be sure that trees, large

shrubs and other plants that provide shade, food or other important

services get first priority.

- Check the long-range weather forecast. If no rain is predicted for the next 10

days – and if your soil is dry – you need to consider watering.

- Check your soil

moisture. Dig

down to a depth of 3-4 inches. If

the soil is dry –and there’s no rain in sight - it’s time to water. Don’t rely on plants to tell you when to

water; you need to check the soil.

At this time of year, the soil should be moist; if not, you need to

water. There is no substitute for checking your soil moisture.

- Check soil moisture

in several places; water accordingly. Shadier, sheltered parts of the garden

remain moist longer than sunny areas.

Be sure to water only parts

of the garden that really need it.

- Water on days that

are cool (or at least relatively so). We’ve had a spate of summery, hot weather this

winter. Check the weather forecast

for days with on-shore breezes and a chance of fog; those are the days to

water. Watering on cooler days

benefits the garden in at least two ways:

- Water is more

likely to percolate into the soil, rather than evaporate;

- Water and warm temperatures encourage fungal and

other plant pathogens. By watering during a cool period you

stand the best chance of avoiding

disease problems associated with warm, moist conditions.

- Water at cool times

of the day. We’ve done well with winter watering

late in the day. The water has time

to percolate into the ground overnight.

- Use watering

methods that decrease evaporation.

Trickle-water with a hose, use soaker hoses or old-fashioned ‘whirligig’

sprinklers that produce larger drops.

Sprinklers that produce a lot of mist waste water.

- Remember that large,

water-wise plants have extensive root systems. Be sure to water out to the

drip-line and beyond. If you’re

using drip irrigation to establish plants, move the emitters out as the

plants grow.

- Install permeable

paving for patios, walkways, etc.

These allow all the water that falls on your garden to percolate in. For more on permeable paving options

see: http://mother-natures-backyard.blogspot.com/2013/06/harvesting-rain-permeable-paths-patios.html

Have

faith – we’ll get through the drought, although our gardens will likely evolve

to accommodate our changing climate.

Look at the drought as a challenge and an opportunity; a chance to make

your garden even more alive and interesting than it is today. Consider ways to incorporate more native

plants in your garden. And for now, if

your Mediterranean climate plants need water, you’ll just have to water.

We

welcome your comments (below). You can

also send your questions to: mothernaturesbackyard10@gmail.com

Tuesday, February 9, 2016

Plant of the Month (February) : Rattlepod – Astragalus trichopodus

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - Mother Nature's Garden of Health |

Despite forecasts

of a strong El Niño season, we’re currently at only about half our normal

rainfall. That’s worrisome! We’ve

been watering Mother Nature’s Gardens, trying to saturate the soils, as they

should be this time of year. One plant

that’s blooming right on target is the Rattlepod, Astragalus trichopodus.

Rattlepod

is known by several common names including Santa Barbara milkvetch, Three-pod milkvetch,

Ocean locoweed and Ocean milkvetch. We

prefer ‘Rattlepod’; a name that well depicts the plant’s most unusual feature. Three varieties of Astragalus trichopodus grow in Los Angeles County. Astragalus

trichopodus var. phoxis grows in

the foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains, but is more common in the inland

foothills of Los Angeles County (San Gabriel Mountains). Astragalus

trichopodus var. trichopodus is

found on Santa Catalina Island and the inland Puente Hills.

Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus – the most common variety in Western Los Angeles County –

was once widespread on the coastal plains and Channel Islands (less than 1000

ft. elevation) from San Luis Obispo County to San Diego County and Baja

California, Mexico. Locally, it once

grew on the coastal bluffs and coastal prairies of Playa del Rey, Hermosa and

Redondo Beach and San Pedro. Specimens

were also collected from the Dominguez Slough (now Gardena Willows Wetland

Preserve). Planting Rattlepod in our

Garden of Health brings this plant home.

We hope to use seeds from our garden to re-populate Rattlepod on the

Preserve.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - growth habit |

Since

Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus is the type grown in our garden,

we’ll focus the rest of this article on that variety. Rattlepod is an herbaceous perennial in the

Pea family (Fabaceae). It dies back to the ground in the dry season,

emerging again with the cool rains of winter and early spring. Once conditions are satisfactory, it quickly

grows to a bushy, somewhat sprawling perennial, 2-3 ft. tall and about 3 ft.

wide. Although the stems are stout, they

are herbaceous. The high winds last

weekend knocked a few branches off the plant in our garden.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - compound leaves |

The

foliage is a bright spring green – the color of garden peas. Like most in the family, the leaves are

compound, with 15-40 rounded leaflets along a midrib that can be up to 8 inches

long (see above). The leaves of local

plants are modestly hairy. We find the

foliage to be unusual and attractive in the garden setting. All

parts of the plant are toxic if eaten. This explains the common name ‘Locoweed’:

domesticated horses, cows and sheep can become quite ill if they eat too much

milkvetch.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - blooming plant |

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - close-up of flowers |

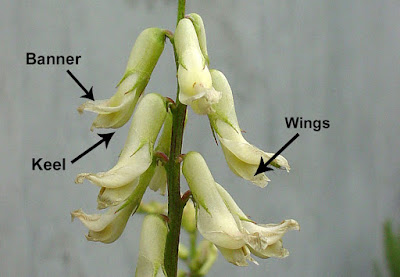

Rattlepod

is an early-flowering species. It can begin

blooming as early as January and almost never flowers later than early April in

our area. The flowers are a waxy cream-white

and are arranged around upright stems. On close inspection (above), the individual

flowers exhibit the usual characteristics of members of the Pea family. You can clearly see the banner and keel on

the photograph above. The early flowers

attract bees and other insects.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - green pods |

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - dry pods |

The

seedpod of Astragalus trichopodus is

rounded and inflated; the dry seeds rattle in dry seedpods, which explains this plant’s

common name. While other vetches have

inflated seedpods, Rattlepod deserves special attention; its pods are puffed up

like little balloons. The pods are 1/4"

to 3/4" wide and 1/2" to 1-3/4" long. Green when young, they gain pink tinges as

they mature, finally becoming dried and tan (see above). Each pod contains up to 20 or so, pea-like

seeds that become wrinkled when dry.

Rattlepod

is very drought tolerant. A long taproot

partially explains this plant’s drought tolerance. But the Rattlepod’s yearly cycle is also

geared to our long dry season. Plants

die back to the roots for the dry period – a pretty good strategy for such an

herbaceous plant. For more on drought

tolerance see: http://mother-natures-backyard.blogspot.com/2015/10/how-things-work-plant-drought-tolerance.html

Local

gardeners on the Palos Verdes peninsula plant Astragalus trichopodus in the hopes of providing larval food for

the endangered Palos Verdes Blue butterfly (Glaucopsyche

lygdamus palosverdesensis). We like the plant because it also attracts

other interesting insects – pollinators, early butterflies and others. The flowers and plant are pretty, and

contrast well with other native plants. Rattlepods

provide good winter-spring fill around larger plants. They also look nice with locally native cool

season grasses, spring annual wildflowers and Wallflowers.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) - Madrona Marsh Preserve |

We are

not entirely sure whether Astragalus trichopodus has medicinal value or not. Asian Astragalus

species are used for a variety of ailments, including viral illnesses.

Chemicals made by several Astragalus species are being tested as possible

cancer and AIDS treatment drugs. That

being said, California native Astragalus species are toxic and should not be eaten. We’ll just have to wait and see whether compounds

from local natives will be added to the medicine bag of the future.

|

| Rattlepod (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus) with Dune Wallflower - Madrona Marsh Preserve |

For a

gardening information sheet see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/gardening-sheet-astraglus-trichopodus

For more

pictures of this plant see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/astragalus-trichopodus-web-show

For plant

information sheets on other native plants see: http://nativeplantscsudh.blogspot.com/p/gallery-of-native-plants_17.html

We welcome your comments (below).

You can also send your questions to: mothernaturesbackyard10@gmail.com

Monday, January 11, 2016

Plant of the Month (January) : Bicolor (Miniature) Lupine – Lupinus bicolor

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - in bloom |

Very

little is blooming in Mother Nature’s Gardens right now. But the recent rains have coaxed a number of

annual wildflower seeds to germinate. We’ve chosen one of these, the Bicolor or

Miniature lupine, as our Plant of the Month.

Like

many native species, Lupinus bicolor

is the subject of current taxonomic debate.

The species shows morphologic variability within its range, and variants

have been categorized as several separate species, as well as varieties and

subspecies of Lupinus bicolor. For simplicity, we’ll just discuss the

species as a whole. Former species which

now are included in Lupinus bicolor are:

Lupinus congdonii; Lupinus polycarpus;

Lupinus rostratus; Lupinus sabulosus; Lupinus umbellatus and possibly

others.

The

geographic range of Bicolor lupine stretches from British Columbia, Canada to

Baja California, Mexico. The species

grows throughout the California Floristic Province (West of the Sierras) and in

the western Mojave Desert. In Western

Los Angeles County, it can be found in the Santa Monica Mountains, on the

Southern Channel Islands and in the Los Angeles Basin from the Transverse

Ranges to the Pacific Ocean. It is a

common in open or disturbed areas from sea level to about 5000 ft. (1500 m.). Like many annual wildflowers, it can be found

in a number of California plant communities including the coastal strand, southern

coastal prairie, valley grasslands, joshua tree

woodland, yellow pine and mixed evergreen forest, and foothill woodland

communities.

Bicolor

lupine is one of about 75 species of Lupine native to California. About one-third of them – including Lupinus bicolor – are annuals; the rest

are perennials, sub-shrubs and shrubs. All

are members of the Pea Family, the Fabaceae.

Like many in this family, Lupines have a unique relationship with special soil

bacteria. These bacteria live within

nodules in the roots and convert nitrogen to a form that can be used by plants,

through a process known as nitrogen fixation.

When the root dies, the converted nitrogen is released into the soil,

improving soil fertility.

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - leaf |

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - plants |

Bicolor

lupine is a small annual, usually less than one foot tall locally, with medium-

to gray-green foliage clustered at the base of the plant. The palmately compound leaves, which look like an open hand, have 5 to 7

leaflets and are covered in short, transparent hairs. The leaf shape is typical for Lupines. As can be seen in the photograph above, the

hairs trap mist and fog quite effectively.

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) flowers & seed pods |

The

flowers of Lupinus bicolor are petite

and charming, making them a favorite small wildflower. This is a fairly early bloomer – often

February or March in Western Los Angeles County, later in colder climates. The flowers, which are usually less than ½

inch across (1/4 to 1 inch; < 2.5 cm.) are arranged in a spiral pattern

(whorl) around short flowering stalks. The flowering stalks, often not much

taller than the foliage, usually have 4-10 flowers per stalk (see above).

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - flower details |

The

individual flowers have a shape typical for the Pea Family, with petals

modified into a ‘banner’, well-defined ‘wings’ and ‘keel’ (mostly hidden). The flowers are two-toned: the banner is white with blue-purple spots or blotches, while the wings are

blue-purple. Like other local lupines, the flower color changes from

blue-purple to red-purple after a flower is pollinated, sending a cue to insect

pollinators that no more nectar is being produced (see photo, above).

Miniature

lupine is insect pollinated, primarily by bees.

The insect lands on the wing petals, causing them to move and reveal the

sexual organs located in the keel. The

pollinating insect brushes against the stamens and

stigma while retrieving nectar, thereby pollinating the flower. The seeds develop in small ‘pea pods’ that

burst open explosively when dry (mid- to late-Spring), spreading the seeds.

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - young seedlings |

Bicolor

lupine is fairly easy to grow from seed.

Like all lupines, the seeds have a hard seed coat; germination is

enhanced by soaking them in hot tap water overnight before planting. Seeds can then be planted in prepared seed

beds or in pots for later transplanting.

Lupines tend to have long roots – in our area they are often easier to seed

directly into the garden rather than transplant. Be

sure to plant seeds on bare ground or under a thin gravel mulch. Plant just before a good rainstorm in late

fall or winter, then rake in lightly; seedlings will appear in several weeks.

Lupines

are an excellent source of nectar for bees, particularly the larger,

early-flying species. The foliage is a

larval food source for Orange Sulphur (Colias eurytheme) and several species of Blue butterflies. The seeds, which are toxic if eaten in

large quantities, are eaten by ground-foraging birds, particularly

Doves. They are an important food from

summer through fall.

In summary, Lupinus bicolor is an annual wildflower that does well

in California gardens and wildlands. It

likes sun, but is not particular about soil type. If winter rains are adequate, Bicolor lupine

needs no supplemental water, completing its life cycle before the summer dry

season.

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) Madrona Marsh Preserve, Torrance CA |

We

like to use Lupinus bicolor along

pathways or in containers, where its small size can be adequately

appreciated. It is often grown, as in

nature, with other local annual wildflowers, California poppies and cool season

native grasses. It is a charming

seasonal groundcover on banks and around rain gardens and infiltration swales.

A

mass of Bicolor lupine, blooming in spring, is a sight for sore eyes. If happy, it will re-seed in local gardens,

returning whenever we have a rainy winter.

Lupinus bicolor is part of our

unique natural heritage and a welcome reminder of the climate cycles that so characterize

S. California.

|

| Miniature (Bicolor) lupine (Lupinus bicolor) - mass planting |

For a

gardening information sheet see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/gardening-sheet-lupinus-bicolor

For more

pictures of this plant see: http://www.slideshare.net/cvadheim/lupinus-bicolor-web-show

For plant

information sheets on other native plants see: http://nativeplantscsudh.blogspot.com/p/gallery-of-native-plants_17.html

We

welcome your comments (below). You can

also send your questions to: mothernaturesbackyard10@gmail.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)